Copper tools predominate in

Sumer by Ur III period (2380-2360 B.C.) In Sumer, the early urban civilization of southern

Mesopotamia, kings used writing to record and commemorate significant military victories.

The standardized equipment of

bodyguards were: a copper helmet, battle-axe, the dagger and a heavy spear. The

early spearheads had long tangs, which were thrust into the spearshaft. A hook was formed

at the end of the tang to firm up the attachment to the shaft. The blade of a Mesopotamian

battle-axe was round, designed to pierce helmets and skulls and slash gaping flesh-wounds.

"Mari on the Euphrates...

The palace administration was responsible for the provision of arms, munitions, and siege

equipment. King Zimri-Lim wrote while on a military campaign to order further supplies of

arrowheads: 'To Mukannishum [his official in the palace] say this, Thou speaks your lord.

When you hear this letter read, have made: 50 arrowheads of 5 shekels [40 grams] weight in

bronze, 50 arrowheads of 3 shekels, 100 arrowheads of 2 shekels, 200 arrowheads of 1

shekels. Give orders to have this done at once. Then have them put in store to await my

further instructions. I suspect the siege of Andariq will be prolonged. I shall write to

you again about these arrowheads. When I do write, have them brought to me as quickly as

possible.' Anothe letter from the king to the same official orders him: 'When you hear my

letter read to you, have made 1,000 bronze arrowheads at 1/4 shekels [2 grams] each. Have

them made from the red bronze at your disposal, and have them sent to me at once.'..

Later, when Shamshi-Adas's son Yasmah-Addu was installed as vice-regent at Mari... in a

letter to his son, Shamshi-Adad ordered 10,000 arrowheads to be made, requiring almost

five tons of bronze. Some of the bronze for the job had to be transported from Assur since

the Mari palace armourers did not have enough stock. The accounts were kept straight

Watkins, 1989, The Beginnings of Warfare, in: General Sir John Hackett (ed.),

Warfare in the Ancient World, London, Sidgwick and Jackson Ltd.)

Sources of tin: the great enigma

of Early Bronze Age archaeology

"The Early Bronze Age of

the 3rd millennium B.C. saw the first development of a truly international age of

metallurgy... The question is, of course, why all this took place in the 3rd millennium

B.C... It seems to me that any attempt to explain why things suddenly took off about 3000

B.C. has to explain the most important development, the birth of the art of writing... As

for the concept of a Bronze Age one of the most significant events in the 3rd millennium

was the development of true tin-bronze alongside an arsenical alloy of copper... That such

(arsenic alloy) ingots would be silver in color and were therefore known as annaku in Akkadian and d'm in Egyptian (E.R.Eaton and H. McKerrell, World

Archaeology 8 (1976): 179f.) is extremely unlikely because the former means 'tin' and the

latter 'electrum'... Many theories have been presented to account for the spread of

metallurgy in the 3rd millennium B.C., through Beaker Folk in the west, torque-bearers in

Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, and Khirbet-Kerak people in the Near East, as well

as Cycladic colonists in Iberia and Trojan prospectors in eastern Europe. Such theories

involve large-scale migration of peoples over vast distances, migrations often identified

with one ethnic group such as Indo-Europeans or Hurrians. It is probably best to reject

all such theories, along with the elaborate archaeological reconstructions that have

accompanied them. There is no evidence to support the existence of any specialized group

of metalworkers in the Early Bronze Age, and it has not been possible to substantiate any

theory of migration or colonization at this time. Even the famous Indo-European migration

into Greece and Anatolia is in need of a comploete reinvestigation... Now everyone, from

the British Isles to India and China, emphasizes the local origins of technology developed

by indigenous cultures. Surely the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction and we are

seeing the extreme reaction to an equally extreme past position. The truth must lie

somewhere in the middle ground... In fact the spread of tin-bronze, the other major

development in copper metallurgy in this period, implies the existence of some type of

long-distance trade. As there are no known sources of tin anywhere in the Aegean, the

Eastern Mediterranean (apart from Egypt), or the Near East, the appearance of tin-bronze

in such widely separated areas as north-western Anatolia (Troy), Cyprus (Vounous), and

southern Mesopotamia (Ur and Kish) requires a network of trade routes covering a

considerable area... The sources of tin being used in the 3rd millennium B.C. remain the

great enigma of Early Bronze Age archaeology... The Old Assyrian letters from the

Anatolian merchant colony (or ka_rum) at Kultepe, ancient Kanes', covering the period

known as ka_rum II, 1950-1850 B.C. , provides extremely detailed information on shipment

of loads of tin (Old Assyrian annukum) from the capital city of Assur to the members of

the private business-houses residing at Kanes'... All that we know is that the tin was

brought to Assur, presumably from points to the east, and from Assur shipped overland by

annual donkey caravans to central Anatolia. We also know that the textiles, representing

the other half of the trade goods sent to Anatolia, came from Babylonia to the south...

With disturbances in the north, especially in the Zagros mountains, cutting off the trade

in tin with Anatolia, Sams'i-Adad I (king of Assyria, ca. 1850-1600 B.C.) shifted his

interests westward and Mari (located on the upper part of Euphrates midway between Aleppo

and Baghdad) became an entrepot on a trade route that brought tin up the Euphrates to

Mari... the texts are vague as to the ultimate source of this tin, but it seems to be

coming from Iran by a southern route through Susa. There is also some indication that

Elamites were involved in the trade... The tin was shipped to Mari in the form of ingots

(Akkadian le_'u) and there stored in various parts of the palace

known as abu_sum (storeroom), the bi_t kunukki (seal-house),

and the kisallu (courtyard)... More evidence on the copper trade

comes from Old Babylonian Ur, where the excavator, Sir Leonard Woolley, uncovered the

house of Ea-na_s.ir, a merchant who specialized in the trade in copper, located at what

Woolley called No. 1 Old Street. A number of texts found in the area and dating to the

reign of Rim-Sin, king of Larsa (1822-1763 B.C.), record Ea-na_s.ir's activities in the

copper trade, which consisted of importing what is called Tilmun copper... called Magan

copper in earlier periods, which was shipped to Mesopotamia up the Persian Gulf. [A. Leo

Oppenheim, The Seafaring Merchants of UR, JAOS 74 (1954): 6-17, and J.D. Muhly,

1973, Copper and Tin, Conn.: Archon., Hamden; Transactions of Connecticut Academy

of Arts and Sciences, vol. 43) p. 221f. ]... However, the shipment of tin all the way from

Iran to southern Mesopotamia and up the Euphrates to Ugarit and beyond to Crete represents

a trade route of epic scope... the so-cakked Dark Age lasting from ca. 1600 to 1400 B.C...

saw the establishment of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni, with its Indo-Aryan background

(T. Burrow, The Proto-Indo-Aryans, 1973, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society,

1973: 123-40)... the recipes for making bronze contained in many Bronze Age cuneiform

texts. The following text from Mari is a good example: (Text is G. Dossin: Archives de

Sumu-lamam, roi de Mari, RA 64 (1970): 17-44, esp. 25, text n.6. The

specification te-ma-yu which appears in several texts from this

archive, is really of unknown meaing). Here the proportions are quite exact: 20 shekels of

tin is added to 170 shekels of copper (almost 1:8) to make exactly 190 shekels of bronze.

This means that there was a fair amount of metallic tin in use during the Late Bronze Age.

By ca. 1400 B.C. tin was being used in Greece to cover clay vases destined for the grave,

in order to make them look like silver, and to line ivory cosmetic boxes to keep the ivory

from being stained by the rouge or ointment placed inside..."

| 1.1/3

MA.NA AN.NA 2. a-na

2 5/6 MA URUDU.LUH.HA

3.TE-MA-YU

4. i-na 8 GIN.TA.AM ba-l[i-e]l

5. SU.NIGIN 3 MA.NA 10 GIN ZABAR

6. a-na nam-za-qi-im

|

1/3 mina of

tin to 2 5/6 minas

of washed copper from

Tema (?) has been alloyed

at the ratio of 8:1

Total: 3 minas, 10 shekels

of bronze for a key

Notes:

takaram = tin, white

lead (Ta.Ma.); t.agromi = tin metal, alloy (Kuwi)

nis.ka = allusion to a

goldsmith (RV. 8.47.15); may also mean gold coins (RV. 1.126.2, 4.37.4, 5.27.2)

loha = red (RV.); lohitaka

= of red colour, reddish (Pa_n.ini's As.t.a_dhya_yi: 5.4.30); lohita_yasa = red metal, copper, made of it (Pa_n.ini's As.t.a_dhya_yi:

5.4.94) Pa_n.ini's As.t.a_dhya_yi: 5.4.94 states that ayas denotes a genus or a

name (hence, may connote metal): anas

as'man ayas saras ityevamanta_t tatpurus.at, t.ac pratyayo bhavato ja_tau sam.jn~a_ya_m ca

vis.aye = anas (cart), as'man (rock), ayas (metal), saras (river) denote a

genus or name; lohita_yasam is a sam.jn~a_ or name; ka_la_yasam is a genus or aja_ti.

ayil = iron (Ta.); ayiram = any ore (Ma.); aduru = native metal

(Ka.)

ayorasa = metal rust (RV.); an:ga_ra = charcoal

(RV.); ayastamba = metallic pitcher (RV. 5.30.15); a_yasi_ =

metallic (RV. 1.116.15, 1.118.8, 7.3.7, 7.15.14, 7.95.1); ayas = metal (prob. copper or

bronze)(RV. 1.57.3, 1.163.9, 4.2.17, 6.3.5, 6.47.10, 6.75.12, 10.53.9-10).

loha: metal that is

extracted (Skt.) cf. Akkadian le_'u = ingots

loha_dhyaks.a =

director of metal work (Arthas'a_stra

: 2.12.23)

ka_rma_ra = metalsmith who makes arrows etc. of metal (RV.

9.112.2: jarati_bhih os.adhi_bhih

parn.ebhih s'akuna_na_m ka_rma_ro as'mabhih dyubhih hiran.yavantam icchati_ )

karmaka_ra = labourer (Pa_n.ini's As.t.a_dhya_yi:ka_rukarma = artisan's work (Arthas'a_stra : 2.14.17); karma_nta = a

workshop or factory (Arthas'a_stra : 2.12.18, 23 and 27, 2.17.17, 2.19.1,

2.23.10). kan- = copper work (Tamil)

d'm = electrum (Egyptian); assem=

electrum (Egyptian); somnakay = gold (Gypsy); soma = electrum

(RV)(See analysis in: Kalyanaraman, Indian Alchemy). |

"According to ratios given

in the texts tin was very cheap, as high as 240:1 and 180:1 in a tin/silver ratio. What is

curious is that bronze was twice as expensive as tin, for a text says of a payment that

'if (paid) in tin (it should be) at the ratio of four minas (of tin) per (shekel of

silver), if in bronze at the rate of two minas.' (Text is Harvard Semitic

Studies (HSS) XIV as quoted in Chicago Assyrian Dictionary (CAD), s.v. annaku, 129a). This seems to indicate a great increase in the amont of tin in

circulation during the period 1500-1300 B.C... One text even refers to an alloy (Akkadian billatu) composed of 1 mina of copper and 8 1/2 shekels of tin, giving a ratio of

7:1. (Text is Keilschrifttexte aus Assur verschiedenen Inhalts 205, quoted in CAD,

s.v. billatu, 226a.) In the Old Assyrian period one text gives a ratio

of 8:1 (4 minas of copper, 1/2 mina of tin, the metal being destined for the smith,

Akkadian nappa_hum)(Text is Cuneiform Texts from Cappadocian

Tablets in the British Museum (CCT) I 37b, quoted in CAD, s.v. annaku, 128a.)

[Notes:

bi_d.u = alloy of iron (Tu.)

pis.t.aka = agglomerate of fine particles (Arthas'a_stra

: 4.3.147)

pa_ka = roasting, cooking (Arthas'a_stra : 4.1.64, 5.2.24)

dravi = smelter or metalsmith who melts metal (RV. 6.3.4: tignam... paras'uh na jihva_m dravirna dra_vayati

da_ru dhaks.at: fire devours wood with

its axe-like sharp tongue, just as the smelter melts the metal).

s'ulva = copper; underground vein of metal ore or water (Arthas'a_stra

: 2.13.16 and 44; 2.14.20-22 and 30-31; 2.12.1, 2.24.1); vellaka = an alloy of silver and

iron in equal proportions (Arthas'a_stra : 2.14.22);

ta_mra = copper (Arthas'a_stra : 2.12.23-24,

2.13.52 and 58, 2.17.14, 4.1.35); na_ga = lead (Skt.);

trapu = tin (RV; Pa_n.ini's As.t.a_dhya_yi:

4.3.138)(Skt.); capala = quickmelting tin or bismuth ore (Skt.);

kan:sa = bronze (RV.);

kajjala = lamp-black used as collyrium (Pa_n.ini's As.t.a_dhya_yi: 6.2.91) an~jana = collyrium (RV.); = antimony compound/sulphide (Arthas'a_stra :

2.11.31, 2.12.6 and 24; 2.22.6)

ka_m.sya = related to bell-metal (Pa_n.ini's As.t.a_dhya_yi: 4.3.168);

a_raku_t.a = brass (Skt.); pittal.ai = brass

(Ta.)]

(See J.D. Muhly, New evidence

for sources of and trade in bronze age tin, in: The Search for Ancient Tin ,

Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978, pp. 43-48)(James D. Muhly, The

Bronze Age Setting, in: Theodore A. Wertime and James D. Muhly (eds.), 1980, The

Coming of the Age of Iron, New Haven, Yale University Press, pp.25-67.)

|

A

warrior, ca. 2500 B.C. with helmet, battle-axe and sickle-sword; a small plaque of

engraved shell from the ancient city of Mari on the Euphrates (Musee National de Louvre,

Paris) |

|

Bas relief, Tello: long

haired person carrying on his shoulder a hooked sceptre; a fillet is held in his left hand

and is presenting it to the warrior standing in front of him with a lance in hand. (Musee

du Louvre, Cat., pp. 87,89 No. 5) |

|

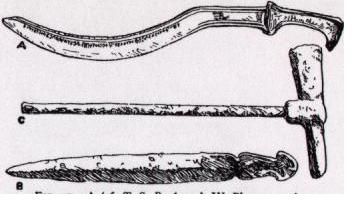

A. bronze scimitar, over

21 in.; length of the blade 16 in. and of the hilt about 5 in., width varies from over one

to just under 2 in.; the hilt was jewelled and inlaid with ivory; bears an inscription of

Adad-nirari I, king of Assyria ca. 1325 B.C. B. Straight sword found at Ashur

C. Bronze axe

(A: Boscawen, 1876, Transactions of the Society

of Biblical Archaeology, Vol. IV, Pl. 2, p. 347; B: cf. Andrae, Der Anu-Adad

Tempel, p. 53; C: Andrae, ibid.)

|

|

Bronze dish found by

Layard at Nimrud: circular objects are decorated by consecutive chains of animals

following each other round in a circle. A similar theme occurs on the famous silver vase

of Entemena. In the innermost circle, a troop of gazelles (similar to the ones depicted on

cylinder seals) march along in file; the middle register has a variety of animals, all

marching in the same direction as the gazelles. A one-horned bull, a winged griffin, an

ibex and a gazelle, are followed by two bulls who are being attacked by lions, and a

griffin, a one-horned bull, and a gazelle, who are all respectively being attacked by

leopards. In the outermost zone there is a stately procession of realistically conceived

one-horned bulls marching in the opposite direction to the animals parading in the two

inner circles. The dish has a handle. (Percy S.P.Handcock, 1912, Mesopotamian Archaeology,

London, Macmillan and Co., p. 256). |

|

Vulture-stele (upright

monument carved with reliefs and inscriptions) of Eannatum, Patesi of Shirpurla, Lagash

leading his troops inbattle and on the march (ca. 2500 B.C.); abandoned bodies are shown

being picked by vultures. [Louvre Museum; Dec. en Chald., pl. 3 (bis)]; inscription

records his victory over Ummaites and treaty of peace forced upon them; upper register:

Ur-Nina, king is of colossal size and is standing; he balances a basket (perhaps

containing clay and foundation brick for the temple of Ningirsu) with his right hand; the

inscription written alongside mentions the temple of Ningirsu; lower register: the king is

raising his cup offering a libation; all figures are clad in Sumerian short woollen skirt,

called 'kaunake'. The light infantry

wear no protective armour and carry no shields; each holds a long spear in the left hand

and a battle-axe in the right. Massed ranks of helmeted spearment are behind a front rank

of men bearing sheilds; these soldiers were trained, uniformed and equipped to fight as

corps.

The vulture-stele shows that the long lance or

spear is grasped by both hands and is the principal weapon of offence. Axe, dart, club or

mace, a curved weapon and a short lance were also in use. Eannatum is bearing the curved

weapon, a number of double-pointed darts and a long lance; he is in the act of piercing

the head of a vanquished foe with his lance, which he holds horizontally over his head at

the extreme end.

Baked clay balls, copper arrows, spears, axes and

stone clubs were discovered in the pre-Sargonic strata at Nippur. |

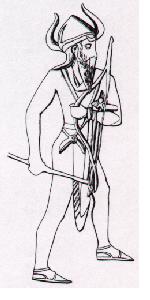

Naramsin with horns of divinity and fully-armed |

Stele of victory of

Naram-Sin, King of Agade (2291--2255 B.C.) found at Susa, whither it had been brought by

the Elamite king Shutruk-nakhkhunte as part of the 'booty of Sippar'; Height 198 cm.; this

celebrates a victory over the Lullubi. In mountainous and wooded country the Akkadian

monarch is depicted at the head of his troops protected by the symbols of his deities.

Wearing a horned headdress to signify his own divinity and carrying a bow, he tramples the

enemy beneath his feetBow and arrow appear to be the principal weapons, apart from the

spear and the axe (note the absence of any type of shield). |

|

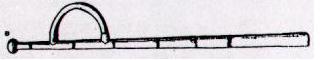

From Tello: Lancehead,

copper blade 31 1/2 in. long, belonging to a lance; the title 'King of Kish' is legible

with the sign 'Sharru'; tang is pierced with 4 holes and a flat surface of the blade is

engraved with the figure of a lion; found six inches above the stratum in which the

remains of Ur-Nina (founder of the first dynasty of Lagash) were buried (Cat., p. 367;

Dec. en Chald., Pl. 5 ter, No.1. Musee du Louvre). Hollow pipe of beaten copper, over ten feet long and dia. of 4 in.; the

tube was fastened to a wooden pole with copper nails; the pipe tapers upwards and the top

is crowned with a hollow ball of hardened bitumen, a little below which there is a large

semicircular handle which is also a hollow tube made of copper; it appears to be part of a

standard as it is found reproduced on the famous vase of Gudea.

[Weapons of copper have been discovered at Nippur,

Fara, Tell Sifr: hammers, knives, daggers, hatchets, fetters, fish-hooks, spear-heads;

some weapons have rivets for wooden handles; also found were: mirrors, net-weights, vases,

dishes and cauldrons] (cf. King, Sumer and Akkad, p. 26; and Hilprecht, Explorations,

p. 156] |

|

Builders' tools carried

by Ur-Nammu of Ur (Harriett Crawford, 1991, Sumer and the Sumerians, Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press, Fig. 4.6) |

|

Assyrian weapons found

represented on bas-reliefs: A,B,C,D

show different kinds of pike wielded by the warriors of Ashur (they vary in length,

handles differ; but all have a diamond-shaped blade).

E shows arrow-heads shaped like the pike.

F shows two extremities of the bow, often

terminating in the head of a bird.

G to L are quivers in which the arrows reposed. L

is the largest and could accommodate five arrows; the normal number seems to have been

four. The quiver was slung over the back by means of cords (cf. G,J,L).

M,N depict swords.

O depicts a curved sword. The sword-hilt was often

adorned with several lions' heads, while the scabbard itself was often decorated with

lions.

P is a sceptre, a ceremonial weapon symbolic of

royalty.

Q is a dirk brandished alarmingly as shown by the

composite monstrosities portrayed on the palace walls of Ashur-nas.ir-pal. |

Gadd Seal 1 |

Seal impression and

reverse of seal (with pierced lug handle) from Ur (U.7683; BM 120573); image of bison and

cuneiform inscription; length 2.7, width 2.4, ht. 1.1 cm. cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp.

5-6, pl. I, no.1; Mitchell 1986: 280-1 no.7 and fig. 111; Parpola, 1994, p. 131:

signs may be read as (1) sag(k) or ka, (2) ku or lu or ma,

and (3) zi or ba (4)?. SAG.KU(?).IGI.X or SAG.KU(?).P(AD)(?) The commonest

value: sag-ku-zi |

|

Seal; BM

122187; dia. 2.55; ht. 1.55 cm. Gadd PBA 18 (1932), pp. 6-7, pl. 1, no. 2 |

|

Seal; BM 122946; Dia.

2.6; ht. 1.2cm.; Gadd PBA 18 (1932), p. 7, pl. I, no.3; Legrain, Ur Excavations,

X (1951), no. 629. |

|

Cylinder seal; BM 122947; U. 16220; humped bull

stands before a palm-tree, feeding froun a round manger or a bundle of fodder; behind the

bull is a scorpion and two snakes; above the whole a human figure, placed horizontally,

with fantastically long arms and legs, and rays about his head. |

|

Cylinder (white shell) seal impression; Ur,

Mesopotamia (IM 8028); white shell. height 1.7 cm., dia. 0.9 cm.; cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932),

pp. 7-8, pl. I, no.7; Mitchell 1986: 280-1, no.8 and fig. 112; Parpola, 1994, p. 181; fish

vertically in front of and horizontally above a unicorn; trefoil design |

|

Seal; BM 118704; U. 6020; Gadd PBA 18 (1932), pp.

9-10, pl. II, no.8; two figures carry between them a vase, and one presents a

goat-like animal (not an antelope) which he holds by the neck. Human figures wear early

Sumerian garments of fleece. |

|

Seal; BM 122945; U. 16181; dia. 2.25, ht. 1.05 cm;

Gadd PBA 18 (1932), p. 10, pl. II, no. o; each of four quadrants terminates at the edge of

the seal in a vase; each quadrant is occupied by a naked figure, sitting so that,

following round the circle, the head of one is placed nearest to the feet of the

preceding; two figures clasp their hands upon their breasts; the other two spread out the

arms, beckoning with one hand. |

|

Seal; BM 120576; U.

9265; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), p. 10, pl. II, no. 10; bull with long horns below an uncertain

object, possibly a quadruped and rider, at right angles to the ox (counter clockwise) |

|

Seal; UPenn; a scorpion

and an elipse [an eye (?)]; U. 16397; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 10-11, pl. II, no. 11 Rectangular stamp seal of dark steatite; U. 11181; B.IM.

7854; ht. 1.4, width 1.1 cm.; Woolley, Ur Excavations, IV (1956), p. 50,

n.3 |

|

Seal impression, Ur (Upenn; U.16747); dia. 2.6,

ht. 0.9 cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 11-12, pl. II, no. 12; Porada 1971: pl.9, fig.5;

Parpola, 1994, p. 183; water carrier with a skin (or pot?) hung on each end of the yoke

across his shoulders and another one below the crook of his left arm; the vessel on the

right end of his yoke is over a receptacle for the water; a star on either side of the

head (denoting supernatural?). The whole object is enclosed by 'parenthesis' marks. The

parenthesis is perhaps a way of splitting of the ellipse (Hunter, G.R., JRAS, 1932,

476). An unmistakable example of an 'hieroglyphic' seal. |

|

Seal; BM 122841; dia.

2.35; ht. 1 cm.; Gadd PBA 18 (1932), p. 12, pl. II, no. 13; circle with centre-spot in

each of four spaces formed by four forked branches springing from the angles of a small

square. Alt. four stylised bulls' heads (bucrania) in the quadrants of an elaborate

quartering device which has a cross-hatched rectangle in the centre. |

|

Seal; UPenn; cf. Philadelphia Museum Journal,

1929; ithyphallic bull-men; the so-called 'Enkidu' figure common upon Babylonian cylinders

of the early period; all have horned head-dresses; moon-symbols upon poles seem to

represent the door-posts that the pair of 'twin' genii are commonly seen supporting on

either side of a god; material and shape make it the 'Indus' type while the device is

Babylonian. |

|

Seal impression; UPenn; steatite; bull below a

scorpion; dia. 2.4cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), p. 13, Pl. III, no. 15; Legrain, MJ (1929), p.

306, pl. XLI, no. 119; found at Ur in the cemetery area, in a ruined grave .9 metres from

the surface, together with a pair of gold ear-rings of the double-crescent type and long

beads of steatite and carnelian, two of gilt copper, and others of lapis-lazuli,

carnelian, and banded sard. The first sign to the left has the form of a flower or perhaps

an animal's skin with curly tail; there is a round spot upon the bull's back. |

|

Seal impression; BM

123208; found in the filling of a tomb-shaft (Second Dynasty of Ur). Dia. 2.3; ht. 1.5

cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 13-14, pl. III, no. 16; Buchanan, JAOS 74 (1954),

p. 149. |

|

Seal impression,

Mesopotamia (?) (BM 120228); cf. Gadd 1932: no.17; cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 132. Note the

doubling of the common sign, 'jar'. |

|

Seal and impression (BM 123059), from an antique

dealer, Baghdad; script and motif of a bull mating with a cow; the tuft at the end of the

tail of the cow is summarily shaped like an arrow-head; inscription is of five characters,

most prominent among them the two 'men' standing side by side. To the right of these is a

damaged 'fish' sign.cf. Gadd 1932: no.18; Parpola, 1994, p.219. |

|  Yale tablet. Bull's head (bucranium) between two seated

figures drinking from two vessels through straws. YBC. 5447; dia. c. 2.5 cm. Possibly from

Ur. Buchanan, studies Landsberger, 1965, p. 204; A seal impression was found on an

inscribed tablet (called Yale tablet) dated to the tenth year of Gungunum, King of Larsa,

in southern Babylonia--that is, 1923 B.C. according to the most commonly accepted

('middle') chronology of the period. The design in the impression closely matches that in

a stamp seal found on the Failaka island in the Persian Gulf, west of the delta of the

Shatt al Arab, which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Yale tablet. Bull's head (bucranium) between two seated

figures drinking from two vessels through straws. YBC. 5447; dia. c. 2.5 cm. Possibly from

Ur. Buchanan, studies Landsberger, 1965, p. 204; A seal impression was found on an

inscribed tablet (called Yale tablet) dated to the tenth year of Gungunum, King of Larsa,

in southern Babylonia--that is, 1923 B.C. according to the most commonly accepted

('middle') chronology of the period. The design in the impression closely matches that in

a stamp seal found on the Failaka island in the Persian Gulf, west of the delta of the

Shatt al Arab, which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

|

Failaka seal. The Yale tablet is dated to ca. the second

half of the twentieth century B.C.... Trade3 on the Persian gulf was in existence well

before that time-- about 2350 B.C.-- when Sargon, the first Akkadian king referred to

ships from or destined for Melukhkha, Magan and Tilmun (Dilmun) at his wharves. in the

Third Dynasty of Ur (around 2000), when trade apparently was centred at Magan. It is even

better documented on other tablets from Ur (from about 1900 and from about 1800),

belonging to various kings of Larsa. At this time the trade was centered at Tilmun...

Cuneiform inscriptions naming Inzak, the god of Tilmun, were found on Failaka and, a long

time ago, one on Bahrein... Failaka can be equated with Tilmun, or at least was an

important part of it. (Briggs Buchanan, A dated seal impression connecting Babylonia

and ancient India, Archaeology, Vol. 20, No.2, 1967, pp. 104-107). Failaka seal. The Yale tablet is dated to ca. the second

half of the twentieth century B.C.... Trade3 on the Persian gulf was in existence well

before that time-- about 2350 B.C.-- when Sargon, the first Akkadian king referred to

ships from or destined for Melukhkha, Magan and Tilmun (Dilmun) at his wharves. in the

Third Dynasty of Ur (around 2000), when trade apparently was centred at Magan. It is even

better documented on other tablets from Ur (from about 1900 and from about 1800),

belonging to various kings of Larsa. At this time the trade was centered at Tilmun...

Cuneiform inscriptions naming Inzak, the god of Tilmun, were found on Failaka and, a long

time ago, one on Bahrein... Failaka can be equated with Tilmun, or at least was an

important part of it. (Briggs Buchanan, A dated seal impression connecting Babylonia

and ancient India, Archaeology, Vol. 20, No.2, 1967, pp. 104-107). |

|

Cylinder seal impression

[elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] |

Cylinder seal impression, Mesopotamia [Scene representing Gilgamesh and

Ea-bani in conflict with bulls in a wooded and mountainous country; British Museum No.

89308] Cylinder seal impression, Mesopotamia [Scene representing Gilgamesh and

Ea-bani in conflict with bulls in a wooded and mountainous country; British Museum No.

89308] |

Image parallels:  Sign 232 Sign 232

m308

Seal m308

Seal

|

|

Cylinder seal

impression; scene representing mythological beings, bullls and lions in conflict (British

Museum No. 89538). |

|

Mcmohan cylinder seal

with six signs,found in 'Swat and Seistan', unrolled photographically and the unbroken

stamp-end of the seal; positive impression of the cylinder showing Harappan inscriptions

(Robert Knox, 1994, A new Indus Valley Cylinder Seal, pp. 375-378 in: South Asian

Archaeology 1993, Vol. I, Helsinki) The

triangle motif is similar to the motif shown on M-443B.

Possible connection with Sibri cylinder seals

(which show (i) a zebu and a lion and image of a scorpion on the flat end (Shah and

Parpola 1991: 413); and (ii) a zebu bull with a geometric pattern of triangles and a

circle at the stamp end).

"The Seistan findspot of this seal is of great

interest. Evidence exists for the movement of Indus commodities, and, therefore, Indus

commercial activities in the direction of western Asia and, in return, from there to the

Indus world.. Evidence for the Harappan penetration of Seistan and farther to southeastern

Iran is scanty but includes at least one other Indus inscription from an impression of a

sherd discovered at Tepe Yahya, period IV A (c. 2200 BC) (Lamberg- Karlovsky and Tosi

1973: pl. 137)" (Knox, p. 377). |